The Enigma of Other People

A sentimental old saying has it that a stranger is just a friend you haven’t met yet. I think that, if I had to choose a single notion that best characterizes my life’s work, it’s that a friend is just a stranger you think you actually know. The impenetrability of even the people you love the best is a source of fascination and, of course, horror for me; perhaps the reason I like books so much, more than any other artistic medium, is that they come closest (maybe?) to channeling the nature of consciousness.

A lot of people have the habit, when they see a photo of a murderer in the newspaper, of saying, “Just look at those cold, dead eyes.” I don’t think there’s a person alive in 2021, though, of whom there aren’t four or five photos you’d say the same about, if the caption beneath them read MURDERER. I’ve written in this space before about how photos lie, but photos of people lie most of all; we like imposing narratives of our own devising on everything, but especially human faces.

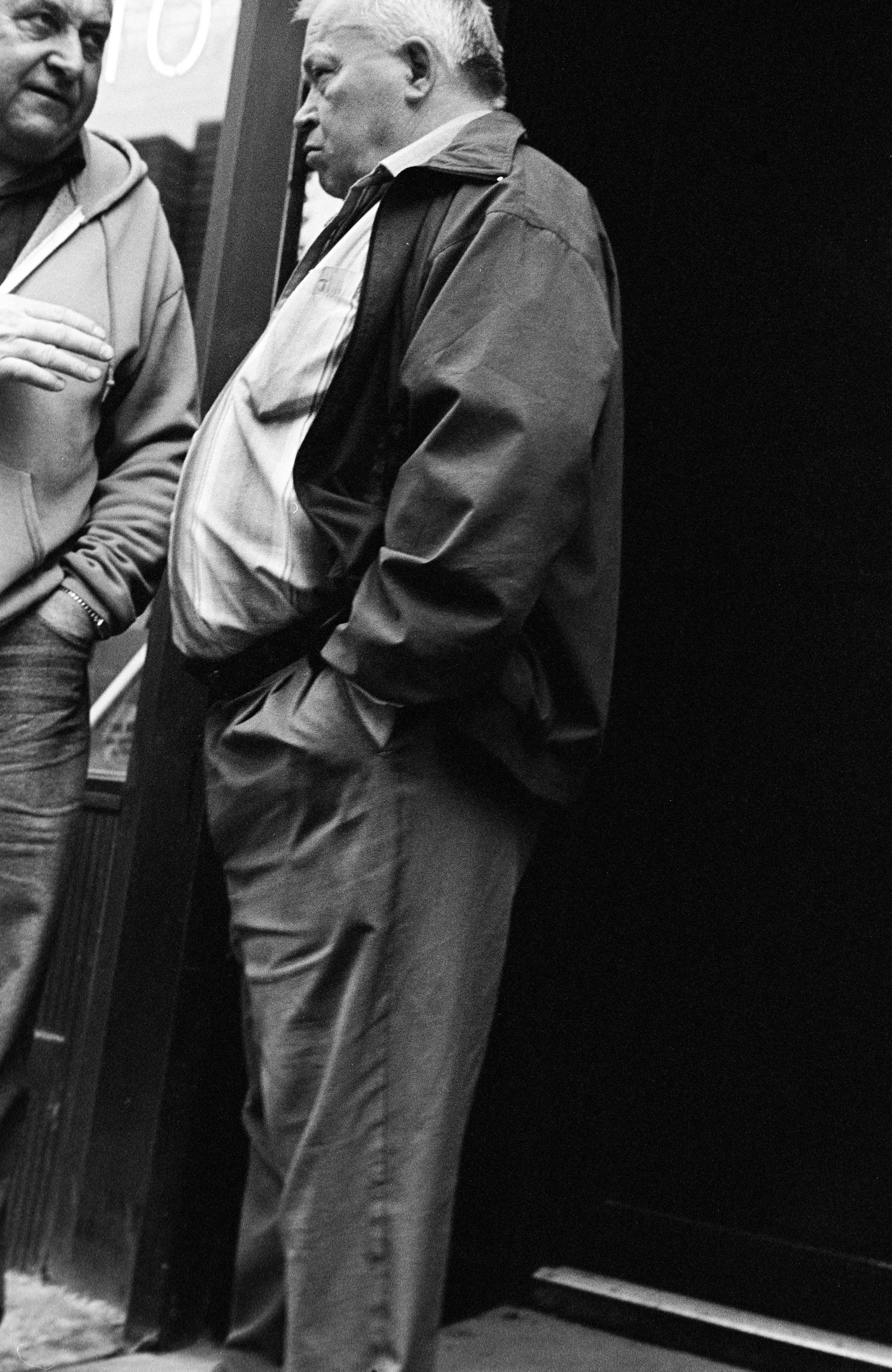

I used to photograph strangers in public all the time. Sometimes I’d use a small digital camera with a wide lens; usually I’d shoot on film. Probably my favorite technique was to shoot from the hip, with a 28mm or 35mm prefocused to about six feet, the aperture around 5.6 or 8, and the camera loaded with ISO 400 film. This gave me a snapshot-ready depth of field at a fast shutter speed, and I’d release the shutter as soon as the subject came into range, without slowing my stride. Rangefinder cameras are really quiet and usually nobody even noticed I was there.

Brooklyn, 2009

I stopped doing this—at least, the getting-up-close method—when a subject confronted me on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, during fashion week. She was wearing a cool coat! And it was fashion week! But she did not want to be photographed. She said what I was doing was illegal, that she could legally demand my roll of film, and she ought to know, because she used to shoot for Magnum. Maybe she had shot for Magnum (home to the most confrontational street shooter of all, Bruce Gilden), but none of the rest was true.

Manhattan, 2010

Still, I hated making somebody feel that way. After that, when I shot in public, I did so at a distance, more discreetly, usually of scenes with no people in them, or in which the people were merely part of a larger composition.

London, 2012

I think of the difference as being akin, in fiction, to the first person or a very close third-person limited rendered in the free indirect style, versus a roving third person over which an omniscient narrator has dominion. I’ve been writing a lot of first person lately, including the new novel, and a thing I’ve begun that might be a novel. In photography, I’m standing back, being an omniscient narrator.

Manhattan, 2009

I think there’s an increasing sense that photographing strangers is creepy behavior. In the mid-twentieth century, when candid street photography was on the rise, a photographer could imagine that a person’s face was an abstraction, an art object; the only place anyone would ever see the photo was in an art gallery or a book. The subject was unlikely to be affected by their having been photographed, or even to know it had happened. Now, publication is instantaneous and globally accessible, and anonymity is dead. Non-journalistic candid photos of strangers feel like an imposition.

Philadelphia, 2016

Of course, fiction, mine included, is full of strangers who don’t know they’re in a book. I don’t think there will ever be an algorithm that will be able to determine that one of my characters is an amalgam of so-and-so’s crooked face, so-and-so’s loud voice, and so-and-so’s wacky sense of style. Of course, those people might read the book and see themselves in it, but in my experience a reader is more likely to read themselves into a book that, in fact, they are not in. Fiction is supposed to be a kind of mirror, after all—we want to draw you in and make you feel invested! We want you to become the characters.

Loveladies, NJ, 2017