Process Notes: "Hold On"

Today I’m going to write about music—specifically, how my old band, The Starry Mountain Sweetheart Band, arranged and recorded a particular song. Readers who are here for the literary content might still be interested, though; the things that are noteworthy about this process, I think, apply to writing as well.

The Starry Mountain Sweetheart Band was active between 2012 and 2015, and consisted of me, Adam O’Fallon Price, Elizabeth Watkins Price, Lauren Schenkman, and Daniel Peña. (In our final year, when the recording in question took place, John Lynch, pictured here, had replaced Peña on the drums.) We played indie rock with lots of vocal harmonies—sort of like Fleetwood Mac or the New Pornographers.

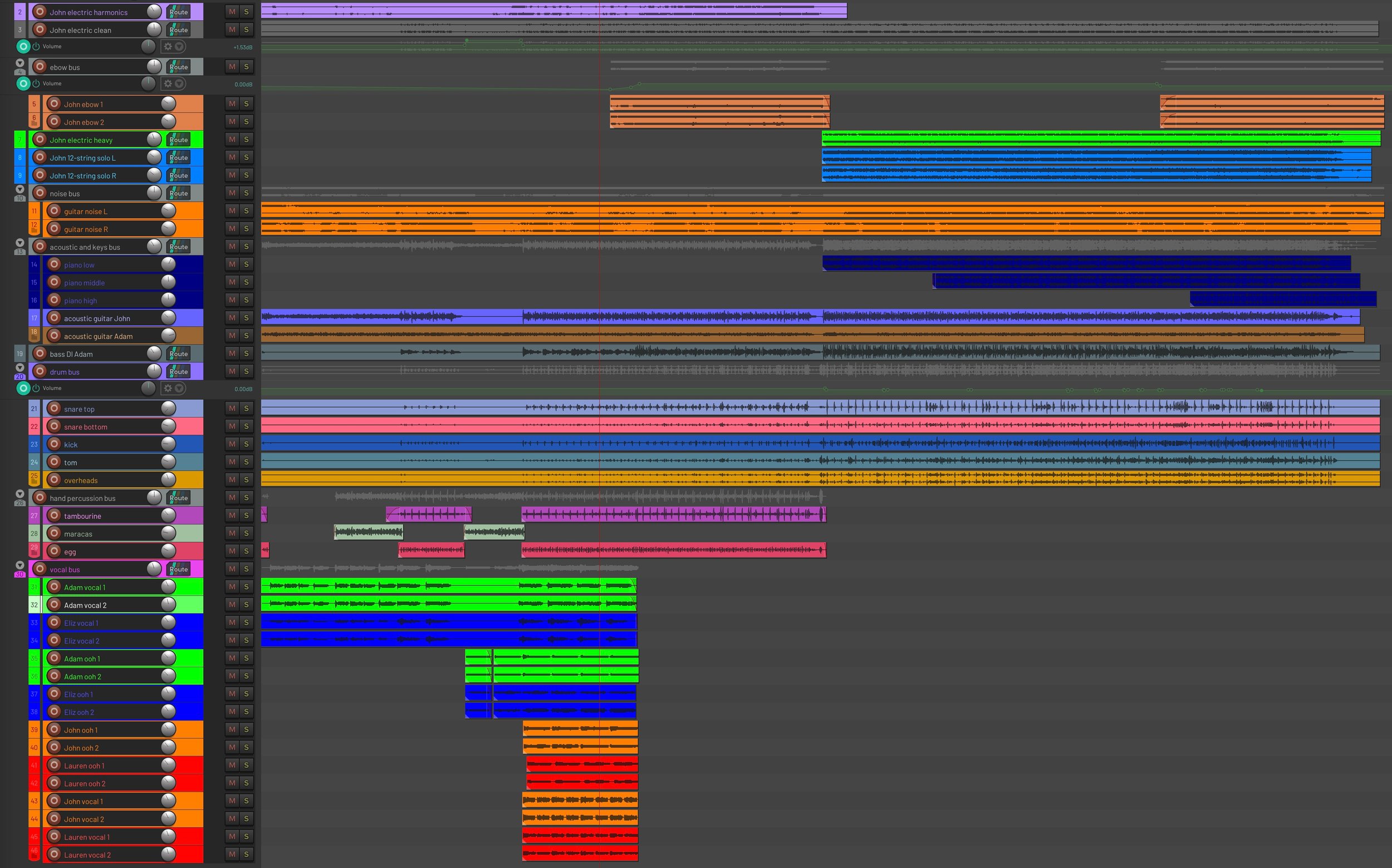

After putting out a couple of albums, we were forced to disband—various members were moving away. But we still had some new songs we wanted to record, that would eventually be released on a posthumous EP. Our usual method was: somebody would write a song and play it at rehearsal, or send out a demo they recorded on their phone. We’d fool around with it until we came up with good parts, then we’d practice and play it at shows. Eventually we’d have a strong arrangement, which we’d commit to a recording. Typically, we’d do a few takes, tracking drums, bass, guitar, keyboards, and a scratch vocal, live in our practice room. I served as recording and mixing engineer, using an Allen and Heath mixing board to capture the performances onto the Reaper DAW (or digital audio workstation, the computer-based equivalent of a multitrack tape machine). Of these sessions, I’d generally discard all but the drums and bass, which I’d edit a little. Then we’d work on the song for weeks, overdubbing stronger instrumental performances, and layering lots of vocal tracks. We favored tight, concise pop arrangements.

“Hold On” was somewhat different. It was the last song we recorded together, over a few weeks in June and July 2015, right before everyone left town. Adam and Elizabeth had written it and brought it to rehearsal back in the spring without much sense of how it should be arranged, only that it should start quiet and spare, and get louder and denser. The song started out with the two of them singing nostalgic, ominous lyrics over Adam’s fingerpicked acoustic guitar:

Now I know the way, and I see the light.

If you love something, better hold on tight.

Hold on.

The world is gonna shake you, baby, that’s no lie.

If you can’t take it, then you’re gonna die.

Hold on.

Then the words became simultaneously more specific and more enigmatic, implying a particular time and place, but without context:

Tennis in the trees in the afternoon,

Everyone I loved left way too soon.

Hold on.

Standing in line and I saw you there,

Fifty-dollar bill hanging in the air.

Hold on.

The chorus was just one phrase—“Is it all?”—with the final word sung in a descending cluster of arpeggios.

The song was pretty, but it wasn’t immediately clear what to do with it. We had a couple of final shows coming up, so we worked out an arrangement: the verses would be quiet, the choruses upbeat, with full drums—and then, after a guitar solo played with an EBow, we’d break out into a long, intense outro featuring chiming guitars, driving piano, and increasingly frantic and bombastic drumming. Adam would switch from acoustic guitar to electric bass mid-song, John would switch from brushes to sticks, Lauren from guitar to piano.

In writing—both mine and my students’—there’s no predictable path to a final product. Sometimes the basic shape of a thing comes to you immediately, and the process that brings it to completion consists primarily of refinement. When this happens, editorial assistance is most valuable writ small: rhythm and pacing, sentence-level tweaks. But at other times, you don’t know what you have, or what, if anything, about it is the good part. You’re more open to people’s broad suggestions, which might send you in a new direction, and to the process of creation itself, which may bring you exciting surprises.

In the case of this song, the arrangement grew out of the shifting tone of the lyrics: from sweetness to mystery to intense emotion. Listening to it, you feel as though the singer is experiencing a catharsis, one that they don’t fully understand. In the opening moments, I pounded on the body of my guitar with my fist, creating a weird harmonic swell. (I was playing a Fender Jaguar, an instrument with some distance between the bridge and tailpiece; if you pluck the strings in this area, you get tuneless, metallic sounds, like a wind chime. I did this, too.) In the verses, John played only a faint, gentle pattern on the hi-hat that evoked ocean waves; in the chorus, he quietly played a steady rhythm on the whole kit. Lauren doubled Adam on the acoustic guitar, and, over the second chorus, joined me in reprising the first verse lyrics in a call-and-response. The superimposition of the verse and chorus made the whole song seem like it was imitating the layered structure of memory—sort of like the way, in fiction, present action can be interspersed with flashbacks.

Recording the song created technical problems. “Hold On” wasn’t a tight pop number; it wouldn’t have benefitted from the kind of meticulous assembly we usually applied to our recordings. Its energy depended on everyone playing at the same time and responding to each other’s cues. We decided to commit to retaining as many of the live tracks as possible. The trouble, though, came with the song’s big dynamic shifts. We were all singing and playing in one room, with the drum and vocal mics open; acoustic and electric guitars were occupying the same space. Everything was liable to bleed into everything else. You could hear singing in the drum mics and drums in the vocal mics—ordinarily an undesirable outcome.

The only solution was to just let it happen; it would be an inalienable artifact of how the song came together. We did two full takes and kept the second. Later, when we overdubbed, the ghosts of the original performances would linger, very faintly, in the background of other instruments. I ended up layering on ten guitar tracks, some just sound effects and drones, over my scratch take. We intended to replace Adam’s initial acoustic take, but ended up leaving it in, behind the overdub. To her original piano take, Lauren layered a second one, one octave higher, and then another higher still. We did sixteen vocal tracks all in all.

Most of what we did here arose not from some strong initial intent, but from reacting to what came before. The song acquired its extended ending—with “Helter Skelter”-style fadeout and return—mostly because John was playing well and we wanted him to keep going. (I left in a bit of studio chatter in the beginning, where Adam is joking with John about the previous take’s tempo, to try and capture a little of the room’s tone and mood.) And during the mixdown, rather than letting the song fade out at the end, I cut off my guitar feedback abruptly, to create the sense that, outside the boundaries of the mix, maybe it just kept going forever.

I don’t mean to discount artistic vision—here, of course, Adam and Elizabeth had started out with an already-good song. But sometimes leaving the work open to serendipitous circumstance can create something really intersting. And technical impediments can necessitate creative workarounds that might ultimately deepen the character of a work.

If you want to hear the whole song, you can stream it on Spotify or Apple Music, or buy the EP via Bandcamp.