Let Me Do My Show! My Life with Billy Joel

This piece originally appeared in Catapult in 2017.

In 1987, the pugnacious singer-songwriter Billy Joel was touring the Soviet Union, as one of the first outside musicians permitted to perform there since the Berlin Wall went up in 1961. The tour was being recorded and filmed, in an effort not only to preserve these historic shows for posterity, but to recoup the tour’s exorbitant costs. Joel was not accustomed to Soviet audiences; they didn’t react to his hits with the same enthusiasm his American fans did. He would later tell a New York Times reporter that the unresponsive crowd at his July 27 Moscow show was akin to “an oil painting.” “I've been on the road for 11 months,” he went on, by way of explaining what was about to happen. “It's difficult. I'm running ragged.”

Joel’s camera crew — the one he had hired to document the tour — roamed the stage, grabbing closeups of the musicians, and generally getting in the way. They had brightly illuminated the first few rows of fans, and to Joel’s mind, this inhibited the show’s energy, and exposed the artificiality of his performance. At one point, during his song “It’s Just a Fantasy,” Joel began to lose his temper.

There is a video of this moment on YouTube. Between sung lines, Joel shouts at the crew: “Stop it! Leave me alone!” Finally, exasperated, he screams, “Let me do my show, for chrissake!” and he tips over his electric piano, which crashes noisily to the floor. The YouTube video cuts some seconds ahead; now Joel’s downstage, a microphone stand in his hands. He raises it above his head and smashes it repeatedly into a stage monitor, while the band plays on behind him. When a cameraman gets too close, Joel goes after him. The cameraman turns and runs, but it’s too late: Joel kicks him in the ass.

“It was a real prima donna act,” Joel later admitted to the Times reporter. “But I have to protect my show.”

*

In the fall of 1983, my grandfather volunteered to drive us all down to Annapolis to watch the Lafayette College football team play against Navy. It would be a longish trip – three hours, at a minimum, if the traffic was light – and there were six of us. So my grandfather acquired a van.

My grandparents Mary and Robert Stein, dancing at my parents’ wedding in 1968

He was a doctor, a Jew, and a prominent citizen, in his day, of Easton, Pennsylvania, the small city on the Delaware River where I was born. If Easton ever had a heyday, it was long past by 1984; it’s one of those towns near enough to New York and Philadelphia to get mired in their effluvia (drugs, poverty, race and class tension), but not close enough to appeal to commuters, or at least the kind of commuters who can stand spending most of their time at home. My grandfather (Robert Stein was his name) was the resident physician at Lafayette, presiding over its student health center and serving as a perpetual sideline presence, stethoscope hung around his neck, at scholastic sporting events. The sight of him running out onto the field when a player got hurt is one of the signature dramatic motifs of my childhood, and one probable reason that my congenital disdain for organized sports remained latent for so long.

Pop Pop was gruff, brooding, mercurial, yet capable of great kindness and generosity. He was also, insofar as this was possible in Easton, a player. He liked to be at the center of things. (His conquest of my grandmother, his rather younger secretary, must certainly have been one of the great social triumphs of his life. I have a photo of them dancing at my parents’ wedding; in it, my grandmother, prematurely silver-haired at 41, is undeniably, devastatingly hot, and my grandfather gazes at her with an expression of giddy, almost unhinged and triumphant love. It was the second and last marriage for both of them.) He also liked to spend money. Objects of mysterious origin routinely appeared in my grandparents’ home, fancy things: obscure and delectable chocolates, the two-inch-thick steaks we ate on Sunday afternoons, bottles of liquor backlit by the deluxe wet bar cleverly built into a hallway of their apartment. Doc Stein collected art, too: I’ve got the Dali now, and Mom’s got the Picasso, and none of us are quite sure what to do about the Frederic Remington bronze cowboy that may or may not have been stolen from a museum in Newark.

My grandfather tended to keep mum about where he got stuff, in part, I think, in order to cultivate an air of mysteriousness and power (he wouldn’t, for instance, let me bring home copies of Omni magazine from the apartment to read, making it clear that he and he alone was their keeper, and that I enjoyed them exclusively at his pleasure), and in part because a lot of it came from local mobsters. He was their doctor; he didn’t charge them, and was remunerated in goods and favors. (Thus the Remington, and the fact that, in those days, I never once saw him pay for a meal in an Italian restaurant.) Indeed, this is how my grandfather preferred to do business: he was a handshake deal kind of guy. So he didn’t rent a van the day we went to Maryland: he sourced one. From a friend who owed him a favor.

The van was awesome. I would love to have it now. It was brown, brown, brown, like a mashup of nineteen-seventies kitchen appliances, and plushly accoutered inside, with leather-upholstered seats and carpeting that I remember as thick pile but was probably not. The point is this, though: my leadfooted grandfather rode the brakes all the way to Maryland, wearing them down to the metal, and we ended up pulling into a suburban mechanic’s garage somewhere outside Baltimore, wreathed in a cloud of acrid smoke. Nobody owed my grandfather any favors here; he and my father had to prod and cajole the mechanic into finding the parts he needed and prioritizing our repair over that of his regular customers.

Even so, we were stuck for a long time, and that van, its back doors open to the balmy fall air, became the crucible of my future adult self. I got angry back there, with my books and tapes and boredom, far from my witty Dungeons and Dragons friends and brutally terrible rock band. I hated football, I realized; I hated road trips, I hated everyone. Familial pressure to attend college (an inevitability I passionately advocated for, yet still somehow managed to resent) was stirring; there would be, post-brake-replacement, many unsubtle hints that perhaps I would enjoy attending the Naval Academy. During those unseasonably warm suburban Maryland hours, my petty resentments would catch fire and begin to change form. Those moments were remaking me into, god forbid, a sort of almost near-man.

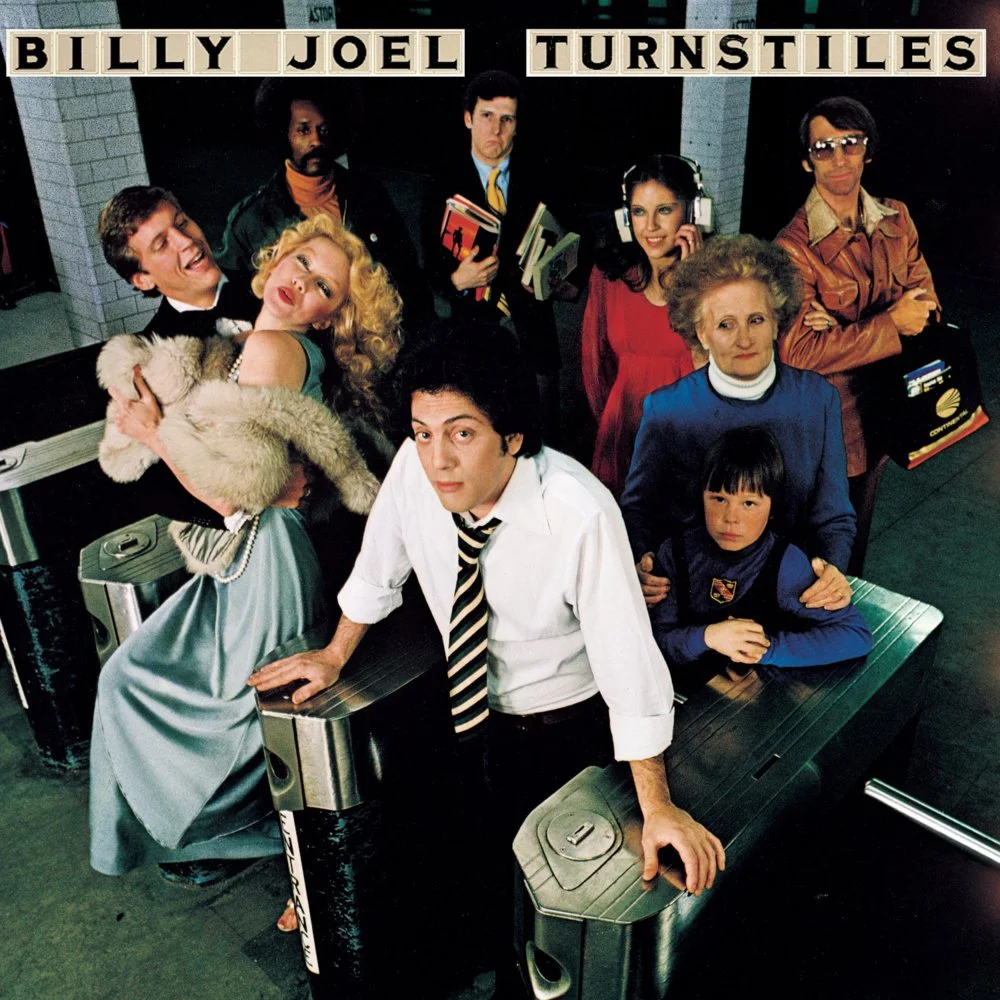

I have no recollection of what I was reading that day, but I sure remember the soundtrack. I had one cassette in my Walkman, a Maxell XLII-S90, which I had impregnated with two LP’s not long before (while sitting perfectly still at the dining room table, obnoxiously policing my family so that their heavy footsteps wouldn’t rumble or stutter the vinyl): Billy Joel’s Turnstiles and Billy Joel’s Streetlife Serenade.

*

Even within the confines of this exercise, wherein I cast my mind back to an era when, free from the contextualizing influence of rock history that now prevents me from unironically enjoying the music of Billy Joel [2025 note: I’m over it, I can just enjoy him now], I cannot say that I ever regarded Streetlife Serenade as a good album. The follow-up to his waltz-in-limericks hit (or, non-hit, as Joel told actor Alec Baldwin in 2012[1]) Piano Man, its maudlin, repetetive title-track opener seems to express envy for performers without a hit album or record label (“Streetlife serenaders / Have no obligations / Hold no grand illusions”), and who aren’t forced by circumstance to get along with others. If this kind of dyspeptic number is precisely the kind of thing you’d expect to find on the third album by an unpopular recording artist, you might not expect it to be followed by so much more of the same. But the whole record’s grumpy: “Los Angelenos” stands up, and then knocks pissily down, a series of stock figures from Joel’s temporary California home (the rich and the vain; the faded and the stoned). “The Great Suburban Showdown” tells the story of his flight back east, which he also doesn’t sound too happy about: “Drive into town / When this big bird touches down / I'm only comin' home to say goodbye / Then I'm gone with the wind.” In “Roberta,” he longs for a prostitute (“Roberta, how I've adored you / I'd ask you over but I can't afford you,” a rhyme of which you can sense the young Joel feeling inordinately proud) and in “The Entertainer” he vilifies his label for a radio edit that took “Piano Man,” a five-minute song that’s two minutes too long, and “cut it down to 3:05.”

In Joel’s defense, Streetlife Serenade was recorded under pressure from the label; the artist admits it’s no good. “I did not have enough time to write new material,” he told Baldwin. “I had nothin’. I was empty.” He agrees with me that the two best tracks on it are instrumentals.

But perhaps Streetlife Serenade is the ur-flop that ignited my lifelong obsession with bad work by people I otherwise admire. The satisfaction one derives from an indisputably successful book or album or film is sweet, to be sure, but sometimes it strikes me as rote, unimaginative. In the case of Joel’s ill-fated third album, anger and jealousy are the engines of failure. To see Joel so hopping mad, and so openly uninspired, was fascinating to my 14-year-old self. As a young songwriter, I would happily scratch out a couple of awful songs exclusively for the empty satisfaction of watching the notebook pages fill up, and the A’s I was earning in English class were less the result of genuine effort than of self-satisfied, condescending cleverness. My teachers were, of course, onto me and my fundamental laziness, but they gave me the grades anyway – not, perhaps, unhatefully – and with those grades I was pathetically content, even proud. The spectacle of Billy Joel sucking was a kind of anti-inspiration, justification for my own dazzling mediocrity. (I’d like to think that, these days, my persistent affection for others’ failures springs from someplace less callow, more collegial. But probably not.)

Side 2 of my Maryland van tape, however, was a different story. 1976’s Turnstiles contained some actual terrific songs, including “Say Goodbye to Hollywood” (not a hit then, not yet; it would come to greater fame in a live, or pseudo-live, rendition five years later on Songs in the Attic) and my personal favorite, the awkwardly titled “Miami 2017 (I’ve Seen the Lights Go Out on Broadway).” The song opens with a fade-in of emergency sirens and pretty piano arpeggios, then tells the story New York City’s eventual destruction and abandonment; the swelling chords give way to a Springsteenian (or at least Rick-Springfeldian) guitar rave-up narrated by haunting vocals rendered otherworldly by a bit of slapback delay. Throw in a couple of breakdowns with kick and crash on the ones, and a trilling piano coda, and boy howdy, you had my attention.

I still love it. Joel called it a science-fiction song, but its melding of the fantastical and terrifying with the mundane (it’s not like the world is ending, everybody just moved to Florida) feels more like a kind of speculative, real-estate-fueled dirty realism.[2]

The rest of Turnstiles is pretty good, too. “New York State of Mind” is perhaps the closest thing to a nightclub standard Joel has written (don’t you dare say “Baby Grand”), and “James” is a nice proto-“Just-the-Way-You-Are” ballad, in the same way that “Prelude / Angry Young Man” takes a few first steps, with its soundtracky dynamic shifts and key changes, toward the bona fide future hit “Scenes from an Italian Restaurant.”

But can we take a closer look at those last two tracks? Because herein lie some of the strongest signs that Joel’s Streetlife Serende fury has not abated, and might never. If Serenade’s anger largely took the form of vague, embittered longing, this record aims a trembling finger at specific characters, a category I think of as People Who Are Annoying Billy. “James” complains of a figure from the past, an ambitious rule-follower of the singer’s acquaintance: “I went on the road,” he sings; “you pursued an education.” Fair enough. From there, though, Joel proceeds to concern-troll the living shit out of this fellow, accusing him of being shallow, cowardly, and “well-behaved,” before asking him, “When will you write your masterpiece?”[3] It’s hard not to read this question as projection. Turnstiles would soon become Joel’s fourth non-hit record, and he had to wonder if Mr. Integrity himself would ever get around to it.

Joel still has plenty of vemon left for his “Angry Young Man,” who is no less callow than poor James, this time because of an excess of integrity: “He refuses to bend, he refuses to crawl / And he’s always at home with his back to the wall.” He’s proud, the Angry Young Man, too proud to do much other than sit around “with his maps and his medals laid out on the floor.”[4] Is there hope for him? Nope. “He’ll go to the grave as an angry old man.”

At 14, I loved this iteration of Joel. I perceived myself as beset by poseurs, bullies, and dum-dums, and was preparing for my years of rebellion, which lay just ahead. What kind of rebellion, you ask? Oh, sometimes, on the bus between my house and the high school, I would untuck my shirt, and then, six hours later, on the ride home, tuck it back in again. Once, I made out in a movie theater with a girl who smoked cigarettes. I routinely hung out with kids whose parents were divorced, and one time, somebody I was with shoplifted from a convenience store. (I bravely denounced the act.) I was banned from a Perkins restaurant for loud talking.

All right, so my rebellion remained imaginary. Maybe it shouldn’t have. Maybe I should have joined my date for cigarettes, untucked my shirt before I left the house. 1984 was the year of Van Halen – a de-fanged, relatively demure Van Halen, at that – but their unbridled sexuality and scarved-and-spandexed stage acrobatics weren’t to my taste.[5] No, it was terror of my own desires that compelled me to prefer the virtuosic, nearly decade-old snit-rock of Turnstiles, even though, if I’d been honest with myself, I would have had to admit that I was James and James was I: conventionally ambitious, deeply concerned about what other people thought of me, hungry for the approval of my superiors. My anger, such as it was, I now read as having been in response not to the people who expected great things of me, but from my own complicity in their expectations. They just wanted the best! And I was the coward who accepted their notion of what that was.

*

In the early eighties, where I grew up anyway, there were two kinds of musicians. There was the kind who, when they wanted to learn to play a song, would listen carefully to it over and over, wearing out the record if necessary, or, if they didn’t have any money to buy the record, waiting until it came on the radio (nightly “top ten at ten” radio broadcasts made this easier than it sounds), and banging away at it until they figured it out by ear. The name for this kind of musician was “actual musician,” or, simply, “musician.”

I was the other kind, the kind who, when they wanted to learn a new song, went to the music store (not the record store, mind you) and bought the sheet music. The band I was in at the time was packed with this kind of musician, that is, “non-musician.” We practiced at Dennis’s house, and I played Dennis’s mom’s electric piano. We mostly performed our own rudimentary tunes, but one of the covers we did was Huey Lewis and the News’ “The Power of Love,” a very easy track with no changes in key or tempo. And yet I had the sheet music for it.[6] I also had the sheet music for “Chariots of Fire,” the “Hill Street Blues” theme, and of course plenty of Billy Joel.

Age 14, with my rock and roll sheet music

My grandparents had arranged for me to take piano lessons, some years before. I had shown an affinity for music, and had been chosen as the Grandchild With Promise, who would be brought up to appreciate the finer things in life. (Indeed, it would be my grandparents who introduced me to New York City, sushi, Philip Roth, jazz, chocolate-covered espresso beans, and fine art.)[7] So my parents bought a piano, which my future indifference to would curdle into guilt every time I walked past the thing, and I began lessons with the stern, patient woman my grandparents had chosen.

Mrs. Goldfarb was an amazing player, at least to my inexperienced ear. All I wanted to do at lessons was listen to her play, although to do so, then return to my own halting efforts, was almost unbearable. The piano wasn’t even Mrs. Goldfarb’s main instrument – she was an even more gifted cellist. Eventually, I would go to hear her play the cello in an orchestra, an experience that demonstrated conclusively to me how hopeless my classical-music aspirations really were, and how undeserving of her attention my playing was.

It was a relief, really. I liked classical music, but what I’d cleaved to was pop, and I started rejecting the sonatas Mrs. Goldfarb assigned and began to bring Billy Joel sheet music to lessons, in an effort, I suppose, to convert the poor woman. Watching her tear gamely through “Pressure” (The Nylon Curtain, 1982) felt like a victory at the time but was akin to the last wild weekend of a dying romance: the rush was intense, but once we’d passed the “Pressure” horizon, the relationship was dead. I quit lessons soon after.

*

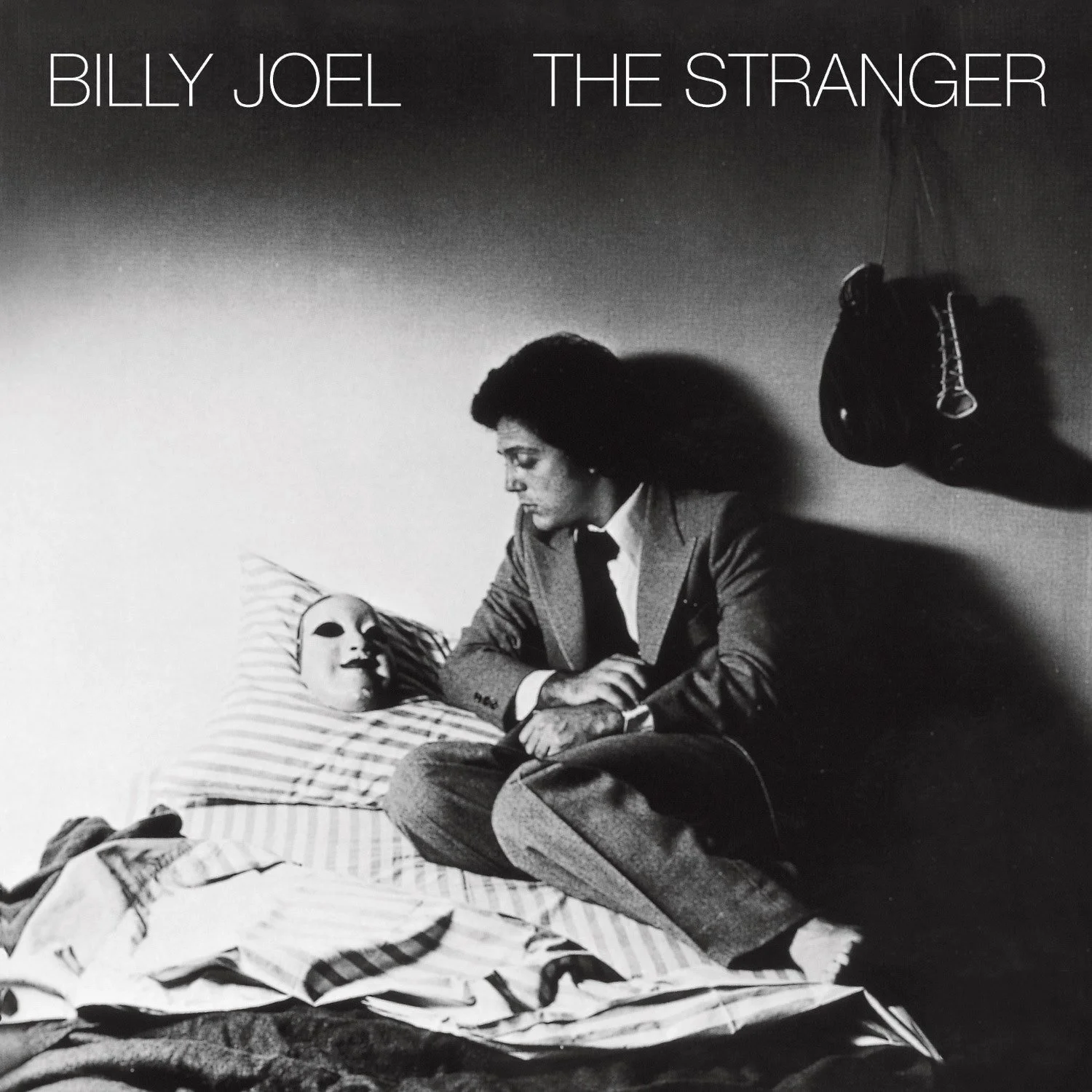

Joel finally had his smash hit in 1977 with The Stranger. It’s the earliest Joel album I can listen through in its entirety today and pretty much fully enjoy, so long as I am permitted the emotional outlet of eyerolls and deep sighs. Its MO is that of neighborhood tales in the style of Springsteen (more on the Boss-Bard binary later), and the anger has been toned down, unless you count the crypto-sexism of “Just the Way You Are” and “She’s Always a Woman,” passive-aggressive ballads that the record-buying public loved, and still does, in much the same spirit, I guess, that they mistake “Every Breath You Take,” The Police’s 1983 smash hit about creepy stalking, for a paean to romantic devotion. They also loved “Movin’ Out” and “Italian Restaurant” and “Only the Good Die Young” (a song my mother, a former Catholic schoolgirl of the very sort the song invites to volunteer for deflowering, detests). But my favorite song on The Stranger is a deep cut, the wistful “Vienna,” a kind of anti-“James” that cheerfuly cautions a headstrong youngster not to sip too eagerly from life’s intoxicating cup.[8] “You’re so ahead of yourself that you forgot what you need,” he sings. “Dream on, but don’t imagine they’ll all come true / When will you realize, Vienna waits for you?”

This sentiment, that life is long and ample pleasures lay ahead for those willing to wait, seems so unjoelisch that you wonder if he’s been tranquilized or replaced. It’s also a rare appearance of an unguarded Joel that shows no hint of anger or bitterness. Indeed, it’s straight-up sweet, like a Paul McCartney song. Actually, come to think of it, it’s like “Hey, Jude.”

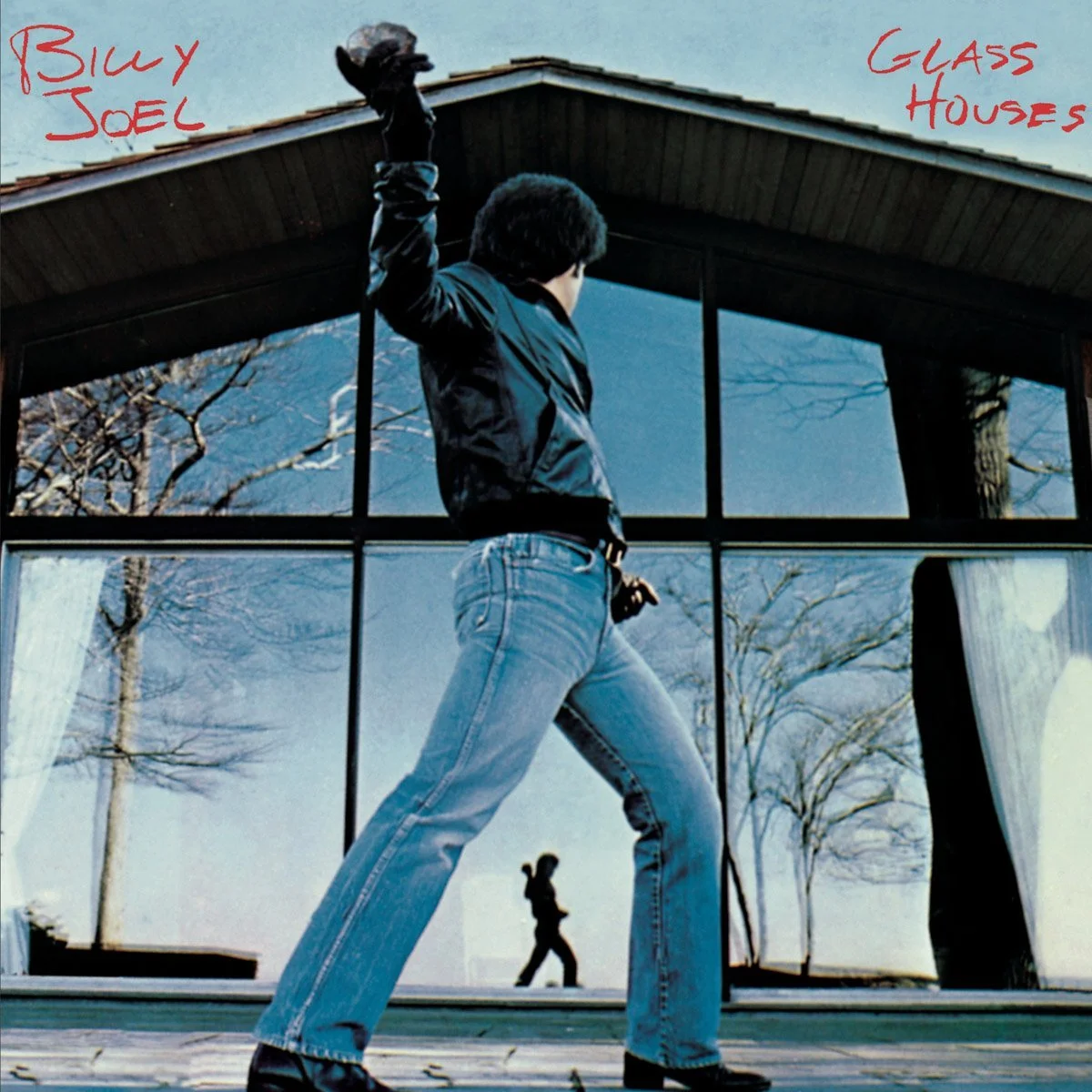

Which brings me to the elephant in the room, for any aspiring Joelologue: his mid-to-late-career penchant for, even obsession with, imitation. Up through, say, 52ndStreet, we get pretty pure draughts of the man. Sure, he’s a bit more derivative than your average hit machine, but everybody raids the Beatles’ catalog for the occasional minor four or descending chromatic turnaround, and that fact that Joel turns everything into a hammily filligreed jazz number is just part of his avuncular charm. But starting with Glass Houses (his best record, I think), and reaching a horrifying perigee on 1989’s awful Storm Front, we can trace the weird spectacle of Joel trying to out-everybody everybody by at first slyly referencing, then openly acknowledging, then mercilessly copping, specific musicians’ styles.

Side one of Glass Houses is a terrific quartet of uptempo rock songs (with a catchy little rhumba, “Don’t Ask Me Why,” wedged into the middle) that begins with the Rolling Stones’ “Street Fi —” oh wait, no, that’s “You May Be Right.” We’ll give that one to Joel; with the seventies drawing to a close and the actual Stones coked up beyond recognition, it was natural to want to inhabit the Stones of 1968, and Joel accomplished it with a fair amount of panache. In the official, live-in-the-studio video for the song, he’s wearing aviator sunglasses and a sport jacket that seems to have been tailored from the remains of the sectional sofa from his grandmother’s half-a-double in Oyster Bay. Joel is sneakered and skinny-tied, and is repping a lot of embarrassingly goofy moves. (He helpfully illustrates the line “Even rode my motorcycle in the rain” by doing a little handlebar dance.) It’s hard not to like him, honestly; he’s trying so hard as, behind him, guitarists David Brown and Russell Javors jointly assume the form of Keith Richards.[9]

Side two opens with two Elvis Costello tunes. It’s hard not to hear it, once you’ve noticed. I didn’t, in my adolescence, because I’d never heard of Elvis Costello. (It would take John Frinzi, my first real musician friend and fellow summer janitor at my old elementary school, to turn me on to This Year’s Model, along with Hüsker Dü and The Replacements; he also eventually sold me my first synthesizer.) “I Don’t Want to Be Alone Anymore” is a calypsofied “Alison”; “Sleeping with the Television On” is “Welcome to the Working Week” with the chorus vocals displaced by half a measure.

The Nylon Curtain opens with a fakeout: its only hit, “Allentown,” presented in the mode of Springsteen, with blue-jean-clad working-class rhetoric and manufacturing sound effects, just in case you didn’t get it.[10] But the next eight tunes are pure psychedelic bombast. Joel has said that The Nylon Curtain is his greatest work; I can see him shouting through cupped hands behind the studio glass: “Phil, baby! I think dis is it! I think dis is my Peppah!” But despite one surprisingly good song (“Laura”), it mostly sounds like Joel is covering the post-breakup Fab Four songbook. His masterpiece is, in fact, the shitty Beatles reunion album Mark David Chapman thought he had prevented.

Then, of course, comes An Innocent Man; Joel acknowledges that the entire album is a self-conscious homage to the his nineteen-fifties influences. By the time he gets to Storm Front, he’s raiding the R.E.M. catalog: “We Didn’t Start the Fire” is a kissing – no, make that a common-law-married – cousin to “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (and I Feel Fine).”

Keep in mind that this man is one of the best-selling solo artists of all time. He has sold more records than Bob Dylan, Stevie Wonder, Paul McCartney, and Prince. He does not have to imitate Elvis Costello and R.E.M. (“At least you’re rippin’ off the greats,” Alec Baldwin quips, 47 minutes into the podcast interview.) Indeed, he has sold, to this day, more records than Springsteen.

*

I am convinced that if there were no Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel would still be writing and recording studio albums. Contemporaries, geographically proximate, near-twins in class and stature, the two men should really not have been able to maintain parellel careers in the arena of piano-, guitar-, and saxophone-based rock music. Somehow, though, for twenty years, they managed. Or, Joel did, in any event. Springsteen merely lived his life as though Billy Joel didn’t exist. But I believe that Springsteen was Joel’s Kryptonite.[11] There were always some similarities in the music, of course, especially in the early days, when Sprinsteen’s records had more piano on them. But ultimately, the Boss (and how Joel must have longed to be so nicknamed by his adoring fans) chose the guitar, and Joel stayed behind the piano.[12]

That is, he usually stayed behind the piano. I can think of one notable exception. It’s the moment that marks, I contend, the beginning of the end of Joel’s recording career, a moment when he made the error of openly acknowledging his rivalry with Springsteen. It is embarrassing to watch, and you can watch it right now. It’s the video for “A Matter of Trust.”

The video opens with a descending crane shot of an ordinary summer’s day in New York: pedestrians strolling down a faux East Village sidewalk, unaware that one of pop’s brightest stars is mere feet away. Cut to an interior: a spacious practice room that is obviously a soundstage, with French windows offering views of the street. Joel is giving orders. “First two chords are open fifths,” he tells the piano player. “Second two chords are open fifths.” (The piano player does not, for some reason, reply, “So you’re saying it’s all open fifths. Why not just say it’s all open fifths?”)

Wait, did I just say piano player? That can’t be! Billy is the piano player! Not this time, friend. Billy’s on guitar: a suspiciously pristine Gibson Les Paul Goldtop. “Okay, girls!” he calls out to the band, none of whom are women. “Matter a Trust!” He makes a Spinal Tap joke to no one in particular, then counts in[13] and starts the song.

Cut to the street. Muffled by the closed French doors, the music barely registers on the jaded pedestrians. This won’t do. Inside, Billy stops playing. “It’s too hot in here!” he says. “Could you guys open the windows?” Windows open, the song begins again.

Reaction shots: heads turn, shoulders twitch. Now, what have we here? we’re meant to believe these people are thinking. That voice...that sound. This is no mere noise; it’s the unmistakeable sonic footprint of one of America’s most beloved rock stars. It’s the great Billy Joel! Heads poke out of doorways, men in undershirts peer down from fire escapes. Cops bark orders into walkie-talkies. A lady in a housecoat leans out a tenement window and shouts, “Shut up!” Back inside, a beautiful woman and an adorable child have suddenly entered the practice space! Could that be supermodel Christie Brinkley, Joel’s then-wife who apparently had nothing better to do, and their two-year-old daughter Alexa? Yes, it could!

For context, this video was produced just a few years after Springsteen’s most iconic filmed appearance, the video for his hit “Dancing in the Dark.” Lip-synced in front of what appears to be a real concert audience, a Springsteen uncharacteristically unburdened by his own signature instrument, the guitar, pulls an “anonymous fan” up from the crowd. It’s actually the actress Courtney Cox, sporting a fetchingly short haircut and a sleeveless Springsteen tour tee shirt, and she chastely jitterbugs onstage with Springsteen as Clarence Clemons pretends to serenade them with the song’s famous saxophone outro.

The video is pretty goofy, but it’s still exciting to watch, mostly due to Springsteen’s seemingly effortless sexiness and self-confidence, Cox’s fresh-faced beauty, and a general air of straightforward American romance and fun. At one point Springsteen hazards a knowing glance at the camera, as if to say, Yeah, this stuff’s pretty stupid, but we’re all havin’ a good time! There’s nothing complicated about the video: the camera stays on Springsteen the whole time, reveling in his moves, his rolled-up sleeves, his tight jeans. There is one subject, one plotline.

Compare and contrast with the “Matter of Trust” video, which, as the title implies, has no trust whatsoever in the charisma of its star. It cannot resist turning Joel’s practice session into a spontaneously transcendent Genuine New York City Street Event, featuring every imaginable stock urban character, and the results are confusing and embarrassing. Continuity errors abound: the SM57 microphone Joel is singing into is positioned at a different angle in every shot, and usually points somewhere between up Joel’s nose and directly at the ceiling;[14] in the crane shots, the crowd is kept far back from the windows, but the interior shots have them pouring through. Joel’s sweat looks like Vaseline, and his Les Paul, we can see in one closeup, is actually autographed by Les Paul. Setting aside the plausbility of anyone playing a rock show, let alone practicing, with a Les Paul that Les Paul has signed, let me say that there is nothing in the world more inherently, appallingly perverse and fake than an autographed electric guitar. Any famous musician who signs one is effectively consigning it to death inside a wall-mounted plexiglas vitrine. And try to imagine Springsteen playing a guitar another musician has autographed. I mean, please. That said, it’s possible to imagine these two videos inhabiting the same contiguous universe, wherein Springsteen puts the guitar down for a moment to film the “Dancing in the Dark” video, and Joel, sensing an opportunity, snatches it and runs away.

But it’s the evidently pointless presence of Brinkley and daughter that really brings Joel’s Springstenvy into focus. It’s not enough that Joel is saying, through this video, Hey, I can play guitar too! Hey, people are cheering for me, too!! He’s also saying, Hey look! I can attract a hot woman too! I actually married one! In fact, I fucked her! The baby is the proof!

This wasn’t the last Billy Joel record or video, of course. But it’s the beginning of the end. The hellhound’s on his trail. His marriage and recording career both have about six years left to go.

*

But who am I to talk? As I write, my own marriage is now in its latter stages of unraveling, and I feel, as I always do,[15] that the death blow to my career is just around the corner. Look, we’re all going to die and be forgotten. I know that. It’s not like I expect, or even want, my work to last forever. But I don’t wish to live out my productive years in a state of terror of the inevitable. Billy Joel didn’t just want to live, he wanted to win, and to stay on top. More importantly, he wanted to be legit, and to enjoy his legitimacy like a seasoned pro. And man, that shit is stressful. The literary figure Joel most resembles is Stephen King, a man once so dissatisfied by his own massive success that he generated a pseudonym to prove to himself he could become famous all over again. It worked, of course. King’s lifelong and embarrassingly obvious longing for approval from the muck-a-mucks at universities, manifest in his tiresome mockery, in his work, of professors, intellectuals, and other cultural authorities, is akin to Joel’s habit of augmenting his songs with snippets of classical piano, as though to remind his listeners he’s no dummy, unlike certain people he could name.[16] Like Joel, King tried to quit writing; but unlike Joel’s retirement, King’s didn’t take. Joel did release one more studio record after his ostensible 1993 swan song, River of Dreams; it’s a collection of neoclassical pieces performed by a legitimately trained pianist, and is called, wincingly, Fantasies and Delusions.

I moved back to the northeast in 1997, after a four-year exile to Montana, where I had studied writing and written my first book, where I met my now-soon-to-be-ex-wife, and where we produced our first child. Before settling in upstate New York, where today we live in separate households, we spent a couple of months in my home town.

I’d seen my grandfather during my years away, of course, but not in the context of his day-to-day life as a minor local celebrity, a condition that had seemed to me inviolable. But like I said, nothing lasts forever. We went out to eat, and people didn’t know who he was. One day I was giving him a ride in the dented and rusted Toyota my wife and I had hauled east behind our rental truck, and something gave way; the car bucked and juddered and ground to a halt on some side street in downtown Easton.

Pop Pop’s disappointment in me was palpable: driving good cars and maintaining them was a family value I’d failed to inherit. Indeed, I’d long felt a little hurt about never being the one my grandfather asked to drive him around on his gray-market errands, this job typically falling to my more automotively responsible father and brother. I wasn’t sure why I’d been recruited this time around, but I had clearly blown it. I apologized profusely, said I’d call Triple A.

Pop Pop stopped me. Don’t, he said. He had a guy. His guy would come. The implication was that the guy would fix the car gratis. He gave me a name and number, and I found a pay phone and called Pop’s guy. “I’m with Doc Stein,” I said. “My car broke down.” The guy didn’t know who I meant, not at first. But eventually I made him understand, and my father came to pick us up.

The car was fixed, eventually, but the work was shoddy and the repair cost $900. My grandfather lived out most of his declining years in Florida, contentedly listening to Danielle Steel audiobooks. Once, I flew there from Ithaca, mistakenly believing that his death was imminent. My grandmother and I sat by his bedside, waiting. At one point, he gestured to me with a trembling finger. Come closer, he seemed to be saying. I took his hand, leaned over the bed. He tilted his face up to my ear, the plastic oxygen tubes creaking and stretching. What would he say? I wondered. What dark truths might he reveal? A family lineage mystery? A secret crime? The true origins of the Remington cowboy?

Through cracked lips, he whispered, “Bring me...some lemonnnn...icccccce.”

*

“Some people think it’s because I’m lazy or I’m just being contrary,” Joel told The New Yorker’s Nick Paumgartner in 2014, on the subject of his apparent retirement from recording. “But, no, I think it’s just – I’ve had my say.” He went on, though, contradicting himself: “You can’t create something that’s an independent entity, made out of whole cloth. They know who you’re in a relationship with, what your past is. They tend to draw their own conclusions. Your image becomes more powerful than the things you create.”

The “they” Joel refers to is his audience: his fans and, of course, his detractors. (I’m mildly ashamed to be both: sometimes a fan, sometimes a detractor, always ashamed.) The “you” he refers to is, of course, himself. It isn’t surprising that Joel employs the universalizing second person here; he wants to think of his decision to stop recording as inevitable, the kind of thing that just happens when anyone finds themselves in his situation. But the fact is, many artists – the ones who keep working – don’t see themselves this way. It’s not necessary to see oneself this way. You can create something out of whole cloth, primarily for yourself, without regard for how it will be received. And it’s possible to think about your audience without making assumptions about what they think about you.

But Joel’s not that kind of artist. “Long ago,” Paumgartner writes, “Joel grew tired of having to look out at the fat cats in the two front rows...guys who’d bought the best seats and then sat there projecting a look of impatience and boredom.” So nowadays, those seats aren’t sold to the public, and before each show, the crew hand-picks pretty girls from “the cheap seats” to occupy them.

Joel’s songs were extensions of his inner adolescent, his bullied and wounded self. His most honest music – not the pastiches, not the bombast, the good stuff – drew upon his insecurities and, unfortunately, his anger. It isn’t surprising that so many of his most passionate fans are people who never grew up, people who remind Joel of the self he wants to leave behind. It must have gotten harder and harder to be honest, the more successful he became: all the cheers did was remind him of who he wished he no longer was. Nowadays Joel plays it safe: his primary language is shtick. He’s got a canned speech for every number, he’s got his jokes and his funny voices. He’s got his motorcycles and his boat and his dog, and people bring him lemon ice whenever he wants it.

*

A meme of recent years invited us to identify our “spirit animal.” My understanding of the term is as a pseudo-shamanistic appropriation, a kind of casual embrace of the familiar spirits of European folklore: supernatural entities in animal form that guide us in our metaphysical pursuits. I guess we’re supposed to feel, whenever we’re doing our thing, whether it’s writing a novel or making a record or roofing or plumbing or whatever, some ineffable bear power or bee power or elk power that is meant to motivate and define us.

It feels like an empty exercise to me, but OK, fine. Just let me ask you this. Does it have to be an animal? I mean, can it be another human? Can it be Billy Joel? Because I think my spirit animal is him.

Or, to frame it as a different passé cultural phenomenon, it’s like I’m wearing a bracelet that reads What Would Billy Do? I don’t usually behave like Billy, at least I don’t think I do, but sometimes my every action feels like a reaction to him. Responding to professional rejection with nervous laughter and awkward standup patter. Finding solace in the creation and dissemination of insecure novelty art. Fucking up my marriage.

I don’t want to do those things, and I don’t want to be the person who has done them. But I guess there’s a limit to how much we can subvert or sublimate our essential nature. Billy Joel is the poster child for this disappointing epiphany: he’s never not Billy Joel to the hilt. At times, I envy him his big, irritating, sloppy personality, his unabashed embrace of his own worst qualities. And honestly, would you want him to be any different?

I wouldn’t have wanted my grandfather to be any different, either, although he and I share a few flaws: hedonistic urges, fiscal profligacy, marital disharmony. He wasn’t actually my grandfather, by the way. My biological grandfather was a physical and psychological abuser whom my grandmother wisely divorced in her early thirties — not an easy thing for a woman to do at that time, or at any time, I guess. But Pop Pop is the grandfather who was actually there for me, and I will admit inheritance of his foibles without shame, even as, every day, I endeavor to tamp down the impatience and anger that is my genetic heritage. I need to believe that a good person can sometimes do stupid things or produce shitty work. I have, after all, to protect my show.

And yes, I proudly claim Billy Joel as an influence, too. Maybe the most important one, who knows. He’s with me every time I try to amuse my children’s friends with a dumb joke, every time I lose my cool, every time I recycle my own ideas or somebody else’s, or otherwise make an ass of myself, and I guess even when I manage to do something pretty good. My first act, upon moving into the divorced-dad condo that is now my home, was to buy a used LP of Glass Houses and give it a spin. Billy Joel is the clown prince of my middle age. He is driving, for better or worse, the brown borrowed van to Baltimore that is my adult life, and riding the brakes all the way.

NOTES

[1] How on earth did this extraordinary cultural artifact, a WNYC-produced podcast interview between Joel his fellow Long Islander, escape my attention for the first three years of its existence? The two men engage in almost unbearably chummy mugging and riffing, telling jokes, doing funny voices, and belting out “In A Gadda-Da-Vida,” and Baldwin can’t resist subtly undermining the great troubaour, needling him about his height and, at one point, correcting his word choice and usage. Anyway, Joel disabuses listeners of the idea the “Piano Man” was, in fact, a hot unit: “People perceive that to be a hit. It was not a hit [...] It was a turntable hit. It didn’t sell through.”

[2] It now seems inevitable that President Donald Trump should take office in the song’s titular year. Damn you, Billy Joel.

[3] At a concert at Hobart and William Smith college in 1996, a fan asked Joel if the song was inspired by a real person. The character, Joel replied, is a composite. “It’s kinda preachy, judgemental,” he admits, then adds, channeling This Is Spinal Tap, that the music is written “in the style of Bach.”

[4] Maps, Billy? The kind you need while crossing America on...a rock and roll tour? And these medals: do they gleam? Are they twelve inches round? Level with us, Billy...are they gold records?

[5] A few years ago, my then-adolescent daughter tried to start her first rock band. The guitarist, an eleven-year-old, came over, lifted a gleaming Les Paul out of its case, and tore into a quite convincing rendition of “Hot for Teacher.” The band didn’t work out. Oh, my child, fruit of my loins, I am so sorry.

[6] While writing this, I became convinced I was making it up. Could there have been a market, in 1986, for such a thing? I looked on the internet, though, and there it was: a simple white booklet bearing the band’s name in drop-shadowed red sans-serif, a rakishly angled live shot of Lewis singing in an era-appropriate blousy geometric print shirt, and the iconic logo of the film Back to the Future, which featured the song.

[7] My grandparents also inadvertently introduced me to MTV, which had become available on their side of the river in Pennsylvania years before it arrived on mine in New Jersey. I’m sure my grandfather longed for me to associate his home primarily with Pablo Picasso and the Modern Jazz Quartet, but Omni and MTV are the things that stuck.

[8] “You're so ambitious for a juvenile,” the singer observes, as though his interlocutor were an underaged criminal offender or a rare species of eagle. Give Joel the choice between a rhyme and a coherent English sentence and he’ll pick the rhyme every time.

[9] Although, Stones snark aside, I think Joel is pretty coked up at this juncture, too. There’s another video, “All for Leyna,” that appears to be drawn from this same filming session, but the studio recording is dubbed over it — Joel is just acting too ridiculous in it to have managed a competent performance of the song. It opens with him slowly rising, like a bug-eyed prairie dog, from underneath his enormous electric piano and synthesizer, and is punctuated throughout by wacky hand motions and Cosbyesque fourth-wall penetration. These antics ought to be anathema to the song’s histrionics, yet it all feels of a piece somehow.

[10] The Nylon Curtain is merely the worst offender in a recording career refulgent with pointed foley work: in this case, industrial clanking and heavy workingman’s breathing on “Allentown,” crickets and thudding synthesized helicopter rotors on “Goodnight, Saigon” (making it sound more like a hospital parking lot in New Jersey, frankly, than a war zone in southeast Asia), and Swedish travel announcements in “Scandinavian Skies,” because, I guess, the title alone isn’t adequately persuasive? None of this, however, can top, for sheer redundancy, the shattering glass sound at the beginning of Glass Houses, cleverly placed to clarify the message conveyed by both the front and back cover images, and by the title, so that it is impossible to miss the ludicrous cliché that is the album’s guiding metaphor.

[11] My friend and bandmate Adam O’Fallon Price, via email: “Springsteen so successfully and adroitly molded his persona, and with BJ it always sounds so forced and difficult. There's such a weight of insecurity with him, this palpable fear of being exposed as this little Bridge and Tunnel chump. [...] I guess I prefer Springsteen's music, but I definitely prefer BJ as a literary character. He's like the Hamlet of successful rock musicians.”

[12] At the keyboard, no one can tell how tall you are.

[13] This is starting to feel like nitpicking now, but it’s worth pointing out that Joel actually sings the count-in. It’s hard to explain to non-musicians how cringeworthy this is. Even including a spoken count-in on a studio recording is in questionable taste (full disclosure: yes, of course I’ve done it), but to assign notes to the count-in, and full-throatedly sing them, is a uniquely Joelian bit of rock-insider foregrounding.

[14] In an ominous prefiguring of Joel’s impending onstage freakout in Moscow, he actually, near the video’s end, knocks the mic stand to the floor. Of course it’s magically standing again a few seconds later, when Joel turns away from it to attempt his own, highly awkward, direct communion with the camera.

[15] As, I suppose, everyone does.

[16] “Me as Tchaikovsky!” he says to Baldwin in the WYNC interview, banging out the opening synth line to “Pressure” on the piano. Later he plays “This Night” and remarks, “You’ll recognize the chorus... which is the Pathetique, by Beethoven!” On the liner notes of An Innocent Man, Joel gives “L. V. Beethoven” co-writing credit for the song.