Distorted Sounds and Words

For its first century or so, audio recording technology dedicated itself to the goal of greater clarity and fidelity—the elimination of distortion. At some point in the nineties, with this goal more or less achieved, the industry pivoted to putting the distortion back in. It turned out we liked it. Engineers accustomed to amplifying sounds with vacuum tubes and recording them to magnetic tape discovered that, in the digital realm, their productions suddenly sounded brittle and anemic; terminology arose to describe the pleasing effects of distortion: tubes and tape, we all agreed, make music “warm” and “fat.” Digital technology, conversely, is cold and thin! The old things were good, and the new ones are bad!

Well—not really. The new things are also good; people just had to figure out how best to use them. Recording engineers still rely on tubes and tape—which have enjoyed a renaissance along with other vintage and retro tech—as well as their increasingly indistinguishable digital emulations. It took a long time to shake the idea that the best reproduction of a sound was invariably the most accurate; often, the fakest thing about a recording is also the most exciting.

I am a fan of digital plugin effects that emulate obsolete forms of technology. Among my favorites are ones that embrace not only the pleasing artifacts of old tech, but their deepest flaws. A vinyl-emulation plugin might recreate not only the subtle sizzle and grind that makes listening to a record exciting; it can give you the scratches and dust, the sound of a streched-out belt or a failing motor. A tape simulator might not offer merely the weight and body of a high-fidelity tape recording, but the ground hum, oxide deterioration, and hiss of a filthy old dictaphone. At one point a few years ago I was bemoaning the unavailability of any plugin that imitated the sound of a worn-out videocassette; not long after, one dutifully sprung into existence.

Part of the appeal of these distortions is, of course, nostalgia for the sounds of our youth; my generation taped songs off the radio with a low-fidelity cassette boombox, and the hopelessly corrupted results remain our head-canonical versions of the era’s hits. But the main appeal is the distance—subtle or extreme—that distortion puts between the music and its listener. Distortion is enigma; it transports us not back to the moment of a sound’s creation, but to the mysterious interstitial zone it has journeyed through. Somewhere between a musican’s hand or mouth and our ears, the music has become something else, something sentient, independent of its creator. I’m fond of artists who take this effect to extremes, like The Caretaker, who degrades and manipulates British prewar ballroom music into a commentary on memory—a mournful, creepy nostalgia for another, forgotten nostalgia. Or Disconscious, whose ambient/vaporwave album Hologram Plaza approximates the watery sound of Muzak echoing through an abandoned shopping mall.

Here is a song of mine," “Whydrops,” that employs a great deal of distortion, both aural and visual, with the intent to unsettle and amuse. The faces you see belong to no one you know; they are inventions of the generative adversarial network behind the website thispersondoesnotexist.com. The treats are real.

Distortion’s analogue in fiction is voice. There is no “pure” form of literary narrative, and nobody would want one: fiction’s appeal derives not merely from what happens, but from the way events are recounted, and by whom. The closest thing we have to “fidelity” in fiction is the third-person omniscient narrator, a stand-in for the author that is assumed to have godlike dominion over the details of the story. But let’s be real: this god is really some knucklehead with a notebook somewhere, and invariably sounds like just another person giving you their version of events.

Voice in third person usually takes the form of so-called indirect discourse, a technique by which the narrator takes on the cadence and syntax of a character whose consciousness it inhabits. The critic James Woods calls this technique the “free indirect style”:

So-called omniscience is almost impossible. As soon as someone tells a story about a character, narrative seems to want to bend itself around that character, wants to merge with that character, to take on his or her way of thinking and speaking. A novelist's omniscience soon enough becomes a kind of secret sharing.

But we most commonly associate voice with the first person, a mode of storytelling that, in its ideal form, gives the illusion of forthrightness—hello, it’s me, the person this happened to, telling you straight!—while employing distortion to tell a different, less immediately obvious tale. We might not be remotely interested in the events recounted in Eudora Welty’s “Why I Live at the P.O.”—the details of a trivial family conflict—if they weren’t being processed through the mind of its eccentric, headstrong narrator:

Papa-Daddy woke up with this horrible yell and right there without moving an inch he tried to turn Uncle Rondo against me. I heard every word he said. Oh, he told Uncle Rondo I didn't learn to read till I was eight years old and he didn't see how in the world I ever got the mail put up at the P.O., much less read it all, and he said if Uncle Rondo could only fathom the lengths he had gone to to get me that job! And he said on the other hand he thought Stella-Rondo had a brilliant mind and deserved credit for getting out of town. All the time he was just lying there swinging as pretty as you please and looping out his beard, and poor Uncle Rondo was pleading with him to slow down the hammock, it was making him as dizzy as a witch to watch it. But that's what Papa-Daddy likes about a hammock. So Uncle Rondo was too dizzy to get turned against me for the time being. He's Mama's only brother and is a good case of a one-track mind. Ask anybody. A certified pharmacist.

I don’t have a favorite kind of distortion in fiction, but the older I get, the more I enjoy creating it, sometimes to the same extremes I do in music. In my last third-person novel, Broken River, I gave my omniscient narrator a kind of secret agent, called The Observer, to foreground the presence of writer and reader, and to investigate the foolishness our own false narratives can lead us to. And the new book, Subdivision, offers a first-person narrator so stubbornly averse to reading between the lines—her own lines, that comprise the book she’s in—that the story itself begins to rebel against her.

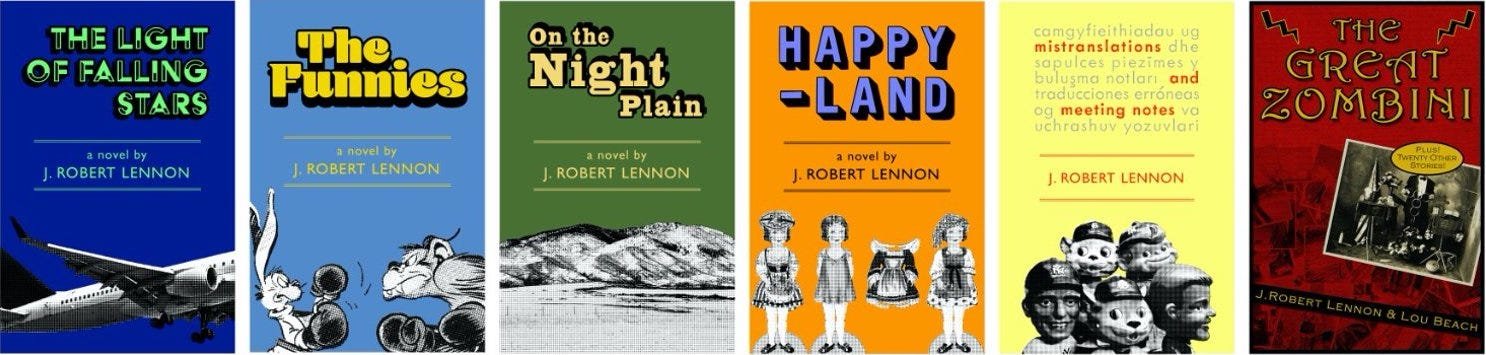

Speaking of my work, there are now ebook editions of all my early novels, available on Amazon, Kobo, and Apple Books. Unfortunately, there’s no print edition of Happyland save for the Harper’s Magazine issues where it was originally published, abridged—but the ebook has a lot of restored content in it.