Just a Guy Made of Dots and Lines

The other day, a writer I know described his struggle to remove em-dashes from something he was working on—he likes to limit himself to one per page, as though they’re cigarettes he’s trying to quit. Em-dashes do resemble cigarettes, or perhaps cigarillos—little dark lines spilled on the white page. Personally, I like to use them often—you see, there’s the third one in this newsletter so far—pardon me, the fourth, I just used another.

Every semester I have to re-explain to students the difference between the compound-word-forming device called the hyphen (there are four in this sentence), and the em-dash, which is typically used as a weak parenthetical—which is to say, like this—or as a casual colon. (Don’t get me started on the 2–3 times a year I have to explain the en-dash, one of which I just deployed.) The em-dash lies along a spectrum of clause-connectors indicating relationships between ideas or events. Others are the period, semicolon, and colon.

These clauses are related. I don’t care to explain why.

These clauses are related; I want to make sure you know.

These clauses are related—get what I mean, man?

These clauses are related: I demand that you notice.

Back in 2012, my friend Bruce Smith gave a great talk on C. K. Williams’s poem “Thirst.” It ended with a riff on punctuation.

Bruce calls the colon a “fascist punctuation mark,” which is not wrong, but he also characterizes it as a pair of sideways eyes the reader is “extruded through.” I wouldn’t know how to argue against that!

The line is the thing that separates poetry from prose, and the thing I envy poets for most. Prose writers can break up text in all kinds of ways: the aforementioned punctuation marks, the paragraph break, the white space, the chapter break. Poets get to have all that, and lines, too. In poetry, enjambment is the term for breaking a line in the middle of a sentence or phrase. Poets use it to create a sense of drama, or to trick you, which are things poets love to do. Here’s Emily Dickinson:

I never hear that one is dead

Without the chance of Life

Afresh annihilating me

That mightiest Belief,

Too mighty for the Daily mind

That tilling it’s abyss,

Had Madness, had it once or, Twice

The yawning Consciousness,

Beliefs are Bandaged, like the Tongue

When Terror were it told

In any Tone commensurate

Would strike us instant Dead—

I do not know the man so bold

He dare in lonely Place

That awful stranger—Consciousness

Deliberately face—

Every line break is a miniature cliffhanger, a chance to create ambiguity and tension. As prose, it would be diminished: I never hear that one is dead without the chance of life afresh annihilating me.

Dickinson used dashes copiously, multifariously, promiscuously. Editors of the distant past figured she couldn’t possibly really mean it and took them all out. The late twentieth century restored them, and now we get to enjoy the spectacle of the great lady smoking as many cigarillos as she likes. Or, if you prefer, eating as many carrots, as in this scrap from Lydia Davis’s short-story-in-fragments “Examples of Confusion”:

I am reading a sentence by a certain poet as I eat my carrot. Then, although I know I have read it, although I know my eyes have passed along it and I have heard the words in my ears, I am sure I haven’t really read it. I may mean understood it. But I may mean consumed it: I haven’t consumed it because I was already eating the carrot. The carrot was a line, too.

In the study of poetry, meter refers to the rhythmic structure of a line, which can be divided into rhythmic units called feet. Each foot has a particular pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. The feet have names and can be illustrated by a series of dots and lines—a process known as scansion. Here are the most common ones, each followed by an English word that embodies it:

Iamb . / (“buffoon”)

Trochee / . (“goombah”)

Spondee / / (“bonehead”)

Anapest . . / (“buckaroo”)

Dactyl / . . (“nincompoop”)

Amphibrach . / . (“jabronie”)

Scanning a line of poetry renders a series of symbols that resembles Morse code, except on high alert, like the fur of a frightened, flea-ridden cat.

A long-standing argument in physics was whether light took the form of dots or lines. Well, all right—particles or waves. It turns out that, like poetry, it’s both. In Subdivision, my forthcoming novel, a man is engaged in a fanciful physics experiment. He’s trying to effect the phenomenon of quantum tunneling on a large scale, by throwing dots (tennis balls) at a line (wall):

To illustrate, the man reached into the bucket on the desk and pulled from it a very worn-looking, much-handled tennis ball. He held it up, meeting my gaze to make sure I saw it. Then, he threw it at the wall. It struck the brick surface, rebounded, and bounced once against the plywood covering the floor. The man caught the ball neatly in his right hand.

This action triggered another line of text on the laptop’s open window:

00038359 no leakage detected. barrier permeability probability 0.000000000000017%.

“Do you see?” the man said, holding up the ball. “Here in the human-scale world of classical physics, the ball bounces back.”

“I do.”

“But in the quantum world,” he now said, shaking the ball for emphasis, “any given particle encountering an ostensibly impermeable surface has a small probability of permeating it anyway. It’s unlikely to happen, but if we try to calculate the path of such a particle, it is impossible for us to achieve an infinitely probable result. It turns out that there is a nonzero chance that such a particle could borrow energy from its surrounding particles, and use that energy to tunnel through the barrier. As I’m sure you’re aware.”

“Of course,” I said. “But I think you’re saying this is only true in the quantum world, not out here where things are large, and abide by other rules.”

The man seemed very excited by this reply. His grin was triumphant, as if I had fallen into an obvious logical trap, and he pointed at me with his ball hand, squeezing the ball in the process.

He said, “That’s what you’d think, wouldn’t you! But the truth is that we are all living in the quantum world! Its logical mysteries are like an infinite-speed bicycle that we’re all riding, all the time, without even knowing it. If there is any probability of a single particle borrowing energy to permeate a barrier, then there is also a probability, however small, that an assemblage of particles—” He held up the tennis ball, triumphantly. “—like this tennis ball, could simultaneously borrow enough energy to permeate another assemblage of particles.”

“I see,” I said.

“In other words,” he went on, his eyes wild, “there is a nonzero chance that, when I throw this tennis ball against that brick wall, it will go right through!” In illustration, he flung the ball at the wall. It bounced back. He caught it. The laptop said:

00038381 no leakage detected. barrier permeability probability 0.000000000000005%.

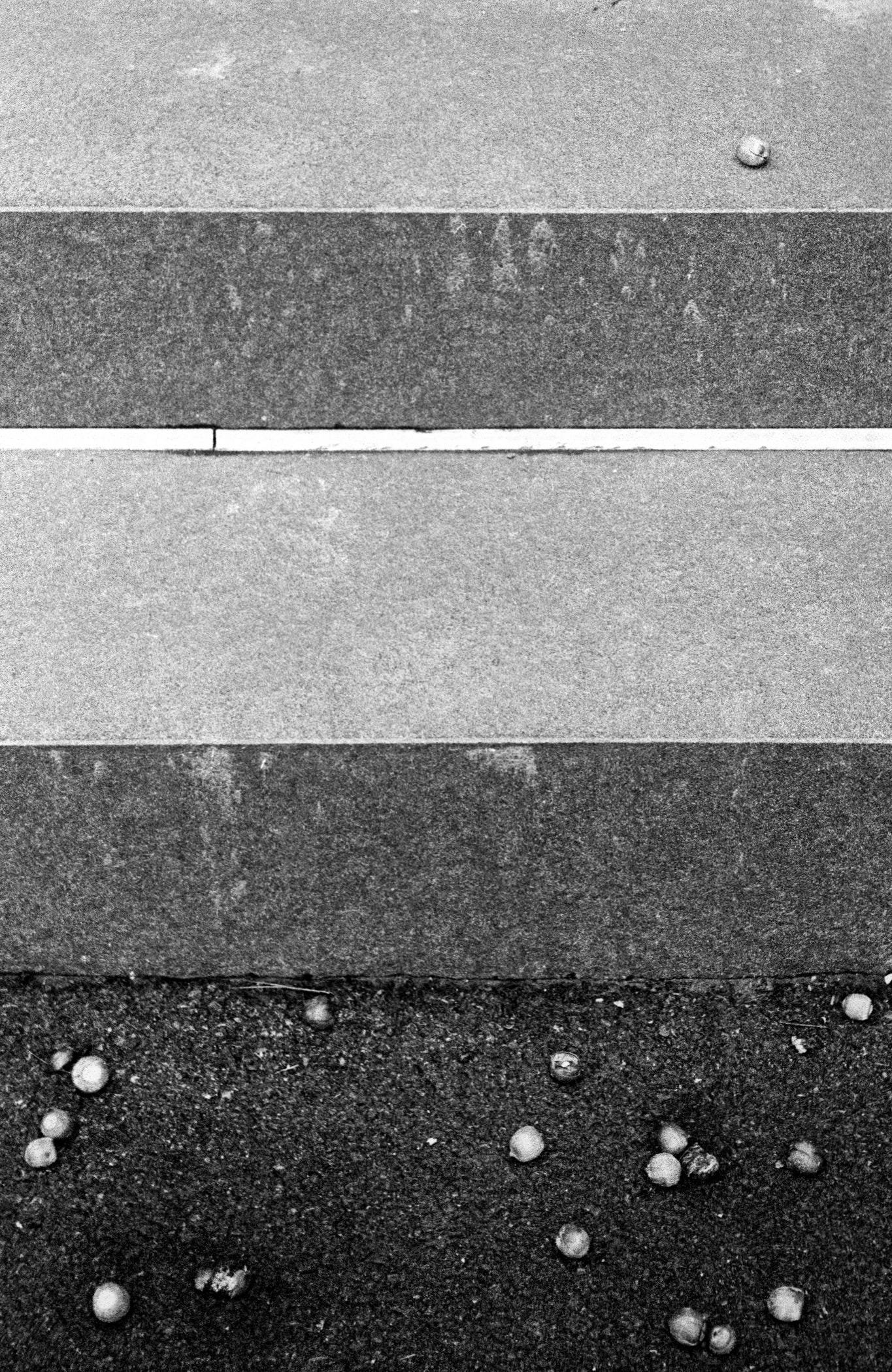

I don’t usually photograph strangers, but I love to photograph evidence of their existence—the manmade environment—especially when it is accidentally beautiful. This beauty often takes the form of dots and lines. Indeed, photographs themselves are composed of dots. Two of the photos below comprise particles derived, during development, from the tiny crystals of silver halide that coat photographic film. The other photo is a collection of twelve million pixels derived from the measure of light that struck each of the twelve million photosites inside my phone. (Want to be pedantic about it? Get in, as they say, line. Of course all three photos are made of pixels now, as you view them on your computer or phone. They are dot-concocted facsimiles of the also-dotty originals.)

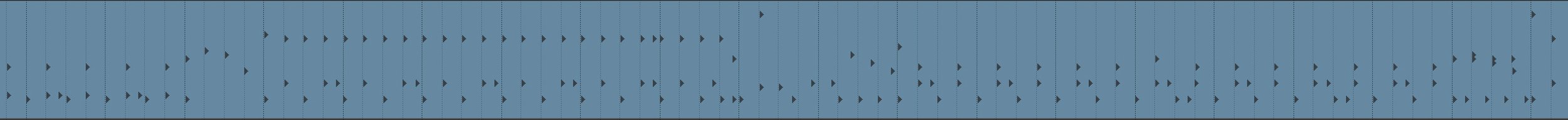

As for music: it used to be (and, sometimes, still is) recorded to magnetic tape, a line of plastic film coated with minuscule dots of iron oxide, which can be realigned via electromagnetism to retain complex sounds. Nowadays, electronic musicians record their performances on a piano roll, a long line of digital dots, representing musical events, that resembles the punched-paper code of a player piano. This is me playing the drums:

The title of this post, by the way, is taken from the They Might Be Giants song “See the Constellation.”